Jonathon Klem

Simplify Your Life With Git Hub Feature Branching

Oct 05, 2014

Recently I started working on a fairly complicated, high-volume Magento website. This website had a development and a production server and the client was juggling several different modifications at once in an effort to boost their sales and improve the customer experience. The problem was, that there was only one development server and they would often like to go back and forth between edits to test functionality out and the experience would come out to something like:

"Let us see what edits #1, #2, #3, #4, and #5 look like..... Ok, let's push #2,#4, and #5 to production." With the nature of how Magento is structured, often the various edits would have a handful of affected files in common.

Previously there was no source code control management in place other than SVN, which was unwieldy and was used mostly to archive stable releases. With the rapid nature of the changes that were coming our way, the decision was made to switch to GitHub, which has greatly simplified the development and deployment process.

Creating the Feature Branch

Now, rather than keeping notes and hoping that everything was documented properly before pushing to production we use what's called the "Feature Branch Workflow". It's a simple 5 step process.

- Create new branch from main source code (referred to as the "master" branch in Git)

- Make modifications to the code in this new branch

- Get client's approval

- Merge this new branch into "master"

- Pull the updated master from GitHub to the production server

The great thing about branches is that you can mix and match features. Before, the client may request feature X which may only be half-way finished and partially broken and the client would make another feature request before feature X was finished that had a higher priority, so they would end up seeing some of X's unfinished functionality on the site while they were testing feature Y.

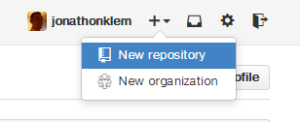

The first step needed to make this happen is to create your repository on GitHub. GitHub offers free public repositories, and for a fee you can make repositories private. Private repositories are recommended, especially if you're dealing with proprietary or sensitive data. You can create a new repository by clicking the plus next to your username.

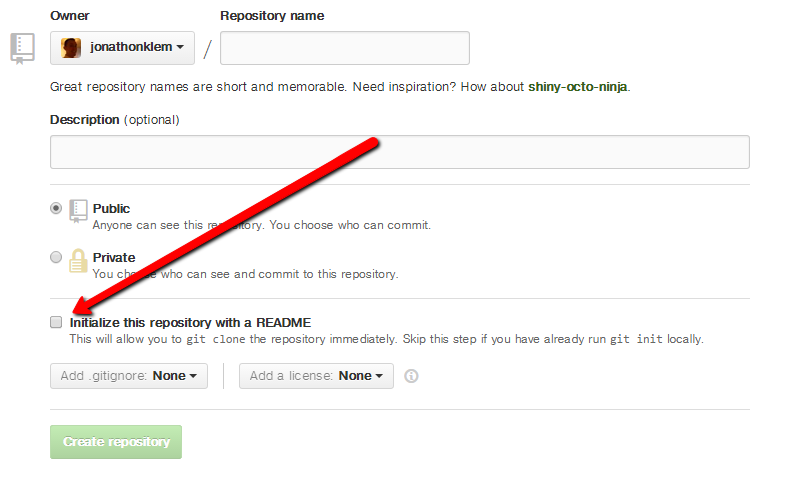

After that, you'll be presented with a screen asking you for information about your repository. I recommend initializing your repository with a README file. As the page says, this will allow you to checkout the repository immediately (we'll cover how to do that next).

Next, you'll be directed to your newly created repository. Here you'll find a link to your 'clone url'. You'll want to copy this and go to your git shell and enter the following:

git clone https://github.com/your_username/your_repository.git

If you're using a private repository, you can add 'username@' between 'https;//' and 'github.com' and it will prompt you for your password.

Now you'll have a directory named 'your_repository' in that directory that you can cd to. Once there you can immediately start working, but this is the master branch. Using the feature branch workflow master should only have stable code. Let's create a branch for our changes called 'featureOne':

git checkout -b featureOne

'git checkout' tells git you're wanting to work with a specific branch. The '-b' option tells it to create this new branch. This command is the more concise form of:

git branch featureOne

git checkout featureOne

Once we're in our branch, we can make any changes we want. For instance:

echo "This is a new file" > test.txt

Once we're done making changes, we'll make a commit. The first thing we want to do is add all the files that we've changed. 'git add' has a '-a' option to add all changed files, but I think this can be dangerous especially when working with large repositories. I prefer to add the files individually:

git add test.txt

Now that our changed file is added, we can commit those changes. First we'll want to commit them locally, and then we'll 'push' those changes to git hub:

git commit -m "This commit message is important"

git push origin featureOne

When you do a 'git push', by default 'origin' is going to be the same address that you cloned. Changing this is outside the scope of this article, but just know that unless you changed it, it's probably going to be 'origin'. After 'origin' comes the name of our branch, with git you can have your local branch named differently than the remote branch that you're pushing to but it's generally a good idea to make sure they match up.

Now, you can see this branch on GitHub. If other developers working on this project wanted to see what was going on with your branch or make modifications to it they could. They could also use the following to pull your new branch into their local repository:

git pull origin featureOne

Testing Branches Compatibility

Ideally this feature would git tested and approved and you could include it in master, but what if the client would also like to see how featureOne and featureTwo work together? We can merge these two branches. It's not a good idea to merge featureTwo directly in to featureOne, but instead we'll create a new branch for featureOneAndFeatureTwo:

#assumes you already have featureOne checked out

git checkout -b featureOneAndFeatureTwo

git merge featureTwo

If you get a message about merge conflicts, you're going to have to wait for my next article. For our simple testing there shouldn't be any merge conflicts.

Once again, we'll want to push this new branch to origin. Git automatically does a commit after you merge, so you won't have to add or commit anything.

git push origin featureOneAndFeatureTwo

You could continue this pattern and stack on as many feature changes as you'd like.

Merging With Master

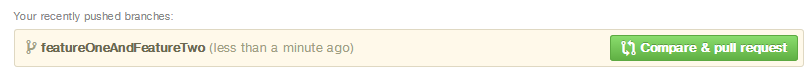

Let's say that the client approves these changes and they like what they see. Our next step is to do a 'pull request'.

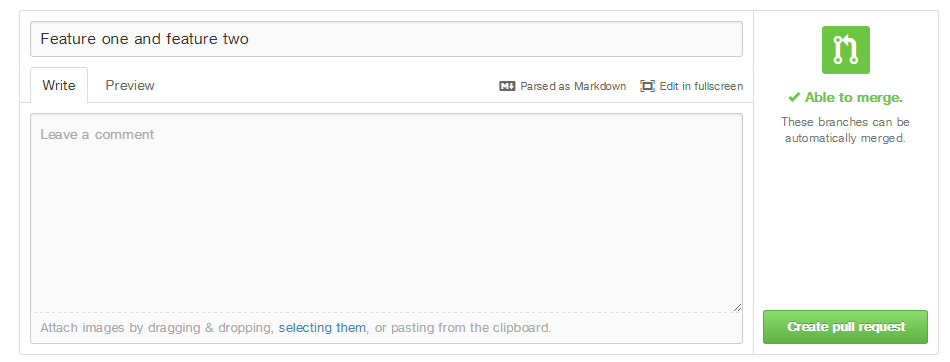

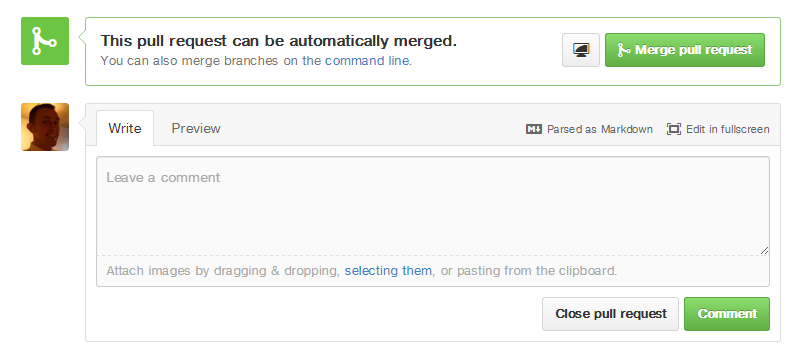

If we click "Compare and Pull Request", we're presented with a screen that lets us add a comment to this pull request:

After entering some comment about our pull request. We can finally approve this. This is also a good opportunity to set up some sort of controls, and allow another developer to review your changes before the pull request is approved. In this example we're going to approve our own pull request:

After we select 'merge pull request', master has our new code in it. If we want to put these changes on production, we can use a simple 'pull':

git pull origin master

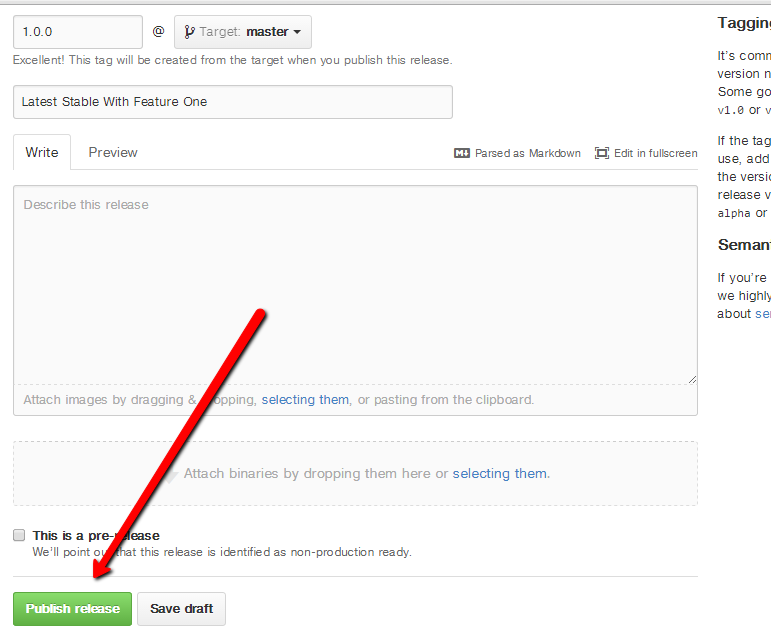

The changes are now synced on production. It's at this stage that I like to 'tag' the release, so that we can revert back to it in the future if we need to. You can find the panel necessary to do this on the main page of your repository.

Next you'll be presented with the option to create a new repository, and from there you will see a form where you can enter the relevant information:

Now, should something happen in the future and some bad commits hit master, we can always revert back to this state.

And that's it! Git Hub's easy branching and merging gives it a significant leg up over SVN and makes it easier to meet client needs and keep track of changes. If you have any questions/comments feel free to email me at jonathonklem@gmail.com. This is the first in what will be a series of github articles.